Main site navigation

Fanny Durack

More information about Fanny Durack can be found in the AWAP register.

From the moment she decided she wanted to be an Olympian, Sarah (Fanny) Durack, set herself on a collision course with sporting authorities and prominent Australian feminists. Born in October 1889 to working class parents in Sydney, New South Wales, Fanny learned to swim at the Coogee Baths and became very good, very quickly in the only stroke for which there was women's competition, the breast stroke. In 1902, at the age of 11, she swam in the 100 yard event at the New South Wales Ladies Championships, a race that was won by another early icon of Australian women's swimming, Annette Kellerman. Fanny finished last, but that would not be a position she held for very long. Over the next few years she became the best swimmer in the country. Eventually, at the 1912 Olympic Games, she proved she was the best swimmer in the world. Given that women could not swim in mixed company in Australia, let alone compete at the Olympic Games when she determined that she was going to be an Olympic Gold Medalist, her achievement was trailblazing by any definition of the term. What is, perhaps, most interesting about the story of Fanny's struggle, is that in Australia it was chiefly women who opposed her along the way.

There are three key themes in the story of Fanny Durack's success, and they all converge in a general discussion of changing public attitudes to women athletes performing in the public arena. The first and most simple theme relates to Fanny's personal drive to be the best swimmer she could be. She loved to swim, she was strong and she excelled at it. She had a good friend, Wilhelmina (Mina) Wylie, whose father owned the Coogee baths, as a training partner, and he encouraged them to be innovators in their swimming. They perfected the stroke that would become known as the 'Australian Crawl' (now commonly known as freestyle). Furthermore, after the restrictions on mixed public bathing were relaxed a little, she and Mina challenged themselves by training with the top men of the day. Fanny and Mina were young women who, by the time they were twenty, had begun to feel that they had done all they could do at home in their sport. They were ready for the next challenge to compete overseas. Fanny was setting unofficial world records in any number of events at home; she wanted them to be officially recognised in an international arena. The fact that she was encouraged along this path by some important men in the swimming world, as well as members of the general public, suggests that, accompanying the success of women's struggle for the right to vote, there had been some baby steps along the road to public acceptance of a woman's right to pursue her private dreams (albeit in social contexts that were severely circumscribed by men), particularly if the attainment of those dreams reflected well in the eyes of the world upon the image of an emerging nation.

The second theme that connects with Fanny's story is that which describes the forces in Australia that were emphatically opposed to her pursuing her Olympic Dream. Mixed bathing was a controversial subject in Australia in the early twentieth century. There is no doubt that by this time, the health and fitness benefits of bathing to men and women were recognised by the majority of Australians. In a nation surrounded by water, it made good sense for people to be confident in it, even women. Indeed, ladies' swimming associations were established to permit women to compete against each other. Leading feminists of the time encouraged women to keep fit and healthy by establishing club swimming meets and learn to swim sessions. Rose Scott, for instance, one of the most important feminist leaders in Australia at the turn of the century, was president of the New South Wales Ladies' Amateur Swimming Association (NSWLASA), an organization that promoted women's involvement in club swimming.

Scott and many of her contemporaries, however, were firmly opposed to mixed bathing. Not only did she disapprove of men and women in the same pool at the same time, she disapproved of men watching women while they competed, even if they were fathers and brothers of the competitors. Scott's opposition stemmed from her total lack of faith in the ability of men to control their sexual urges, a lack of faith built on a career in feminist activities that had seen the damage done to women by sexual predators. She had absolutely no doubt that men bathing with women and watching them in their costumes would put women in the community at large in grave sexual danger. Her opposition to mixed bathing was motivated by an immediate concern for the modesty of the swimmers. 'A girl who is in the habit of exposing herself at public swimming carnivals is likely to have her modesty hopelessly blighted,' she told members of her association. It was also motivated by a concern for all the women who didn't swim, but who could become the innocent victims of the unrestrained sexual impulses stirred up in the men who watched female swimmers. 'I am afraid that the recission of the rule [preventing mixed audiences] will lead to a loss of respect for the girls and the increasing boldness of the men', she told newspaper reporters in 1912. Not all women's groups endorsed this view; nor did the Mayor of Randwick, the municipality where Wylie's baths were located and therefore, the Mayor who permitted mixed bathing there so that Fanny and Mina could train with the men. In his view 'swimming was the sport of the future' and one that all should enjoy. Furthermore, he noted that the female body had 'inspired great painters and sculptors and was not a matter for shame or seclusion'. To a large extent, Fanny had grassroots community support. Nevertheless, if one is fighting a powerful international sporting organisation for the right to compete under their jurisdiction, it helps to have the support of your representative organisation at home. The NSWLASA were totally unsupportive of Fanny's campaign to compete at the Olympic Games. In the view of some, it was right and proper that they should remain so 'the fabric of society' was at stake here, according to the Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, all because a couple of girls wanted to prove they were the best swimmers in the world.

The third important thread in the story relates to the international context; that of the Olympic movement itself. By definition, competing at the Olympics would mean competing in a sporting activity at a mixed event. At the turn of the century, there was still firm opposition to this happening. This was partially because Baron Pierre de Courbertin's vision of the modern Olympics, which he revived in 1896, was a white, masculine one. It was shaped by his interest in the Ancient Greeks and their admiration for white, masculine, athletic bodies. Brought up in France, where women's sport was virtually non-existent, he saw no place for women at the Olympics except as spectators. The Olympics, in his words should be 'the solemn and periodic exaltation of male athleticism with internationalism as a base, loyalty as a means, art for its setting, and female applause as its reward'. Furthermore, in accordance with contemporary understandings of femininity, 'real' women were not 'Amazons' and athletic exertion would only harm them and impact upon their ability to be wives and mothers, a view that medical science and many men and women of the time endorsed. Matters of the impropriety of mixed activity didn't even enter into the equation in the early days of the Olympics. Even if it could be arrange that events were segregated, women shouldn't be there, for the sake of their own health.

Over time women athletes chipped away at the rationale that justified their exclusion. In 1904, at St Louis in the United States, female archers wearing long skirts and blouses were allowed to compete; in London in 1908 women who participated in seemingly demure sports, such as gymnasts, figure skaters and tennis players were permitted to compete, providing they were well chaperoned. Durack herself would have been ready to compete in 1908, but there was still enormous opposition to the prospect of women swimmers competing. What they wore was too revealing; what they did was too 'un-feminine'.

However, just as public opinion in Australia was coming around to support the right of women swimmers at all levels to appear in public in mixed settings, so too was the international sporting community divided over the issue of allowing women to compete at the Olympics. The International Olympic Committee itself was divided over the matter, and in the lead up to the 1912 games in Stockholm, de Courbertin lost his fight to keep women swimmers excluded. In an historic decision, the committee voted in favour of staging two women's races and a diving event, thus opening the way for Australian, American and European women to compete against each other.

The stage was set for Durack to realise her dream. Based on her recent performances, she would have, arguably, been one of the first people to be selected for the team, let alone the first women. Unfortunately, this was not to be the case. When the team was announced, Fanny Durack was not amongst the names read out; apparently the selection committee could not afford to send female competitors. They also fell back on the arguments pushed by Rose Scott and the NSWLASA to explain her omission; that in Australia, the public believed that competitive swimming for women should remain a segregated affair. Durack, Wylie and their supporters, of course, disputed this point of view strenuously, but not a single men's organisation took up their course. Even though the international structures were in place to allow women swimmers to compete, key Australian organizations stood in the way of the world's best female swimmer doing so.

The Australian Olympic Committee and the NSWLASA badly misread public opinion; Durack's exclusion was seen as a national scandal. Women's clubs organised rallies, petitions and funds, while the press gave the affair plenty of prominence in the editorial and commentary pages. Unsolicited donations poured in from the public, determined to see that a lack of funding could not be used as an excuse. The sporting and theatre entrepreneur, Hugh McIntosh was encouraged by his wife to co-ordinate the fundraising effort. The NSWLASA and Rose Scott, in particular, became targets of ridicule, until the association relented and endorsed their champion swimmer, making it possible for her to go. Scott did not agree with the decision and immediately resigned her post as President, maintaining to the end that she thought it was 'disgusting that men should be allowed to attend. We cannot have too much modesty, refinement or delicacy in the relations between men and women…this new decision will have a very vulgar effect on the girls, and the community generally.'

Given that the money was there, the NSWLASA decision removed the final obstacle to Fanny's participation. She sailed for London and then onto Stockholm where Fanny Durack went on to become one of two Australian gold medalists by winning the 100 meters freestyle. She swam in an unmarked pool, with no lane ropes and water so murky that the bottom of the pool was not visible. She also swam in the company of Mina Wylie, who won the silver medal. The Australian Olympic Committee made a last minute decision to send both her and her father to be official coach. Along with Fanny's sister, who went along as chaperone, they comprised the first ever Australian Olympic Ladies' Swimming Team.

Fanny and Mina arrived back to great fanfare and celebration - Fanny was a national heroine, who had achieved her personal goals while paving the way for the host of champion Australian women swimmers to follow. Following her Olympic success, she toured the United States and did more to promote swimming than any woman with the possible exception of her Australian countryman Annette Kellerman. On a U.S. tour in 1912, Miss Durack got newspaper billing as 'holding all championships for deep diving and for staying under water continuously.' Between 1912 and 1918 she broke 12 world records.

By the time she stopped touring, the controversies surrounding her entry into the pool seemed old-fashioned. The fabric of society hadn't frayed too badly and women athletes went on to be wives and mothers. There were still fights to be fought, however. Just as she was leaving, the problems of defining who was an amateur and what constituted professionalism in sport were creating divisions in the swimming world, and Fanny herself was at the sharp end of some of the arguments. Durack retired from swimming in 1921 when she married Bernard Gately at St Mary's Cathedral in Sydney. She went on to coach juniors, and she became an excutive member of the organisation that once made life so difficult for her, the New South Wales Women's (no longer Ladies'!) Amateur Swimming Association. She died in 1956.

Fanny was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1967. According to her citation, she 'not only took on all comers the world over, but beat all comers the world over for 8 years in the formative years of women's swimming. She did more than any other swimmer to make the term "Australian Crawl" a definition which survives until this day'. Sarah 'Fanny' Durack is an Australian sporting legend and an icon of Australian swimming. She is also an extraordinary role model for anyone with a dream.

Image

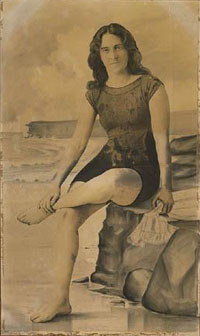

Portrait of Fanny Durack

Image Courtesy of the National Library of Australia, nla.pic-an10716253