Main site navigation

Isabel Letham

'He paddled on to this green wave and, when I looked down it, I was scared out of my wits. It was like looking over a cliff. After I'd screamed "oh no, no!" a couple of times, he said: "Oh, Yes, yes!" He took me by the scruff of the neck and yanked me on to my feet. Off we went, down the wave.'

This is how Isabel Letham remembered the moment that would ultimately make her an icon of Australian women's surfing history. In January 1915, Duke Kahanamoku - 'The Big Kahuna' - the man generally regarded as the inventor of modern surfing, visited Sydney's Freshwater Beach to conduct an exhibition of the new sport. The event attracted an enormous crowd, with fifteen year old schoolgirl Isabel Letham amongst their number. After three hours of entertaining the audience on his own, the Duke called for a volunteer to help him demonstrate tandem surfing. Isabel was chosen and, as a result, she goes down in history, not as the first Australian surfer to ride Hawaiian style - a common misconception that she never promulgated herself - but as an early Australian female surfer who experimented with riding a surfboard in the Hawaiian style.

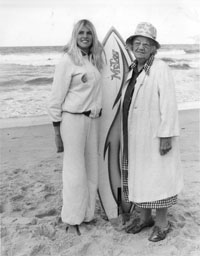

Whether or not she was the first, or one of the first, it is indisputable that Isabel Letham had a long term impact on on the surfing world. She was an inspiration to young Australian women, like Pam Burridge, who dared to break into to the masculine world of professional surfing in the 1970s and 80s. When Burridge won the inaugural women's surfing championship in May 1980, Isabel, at age 80, was present to see her claim victory. 'I should be home with my knitting,' she said, 'but I've waited 65 years for this.' Burridge honoured Letham by naming her first daughter Isabel; the Australian Surfing Hall of Fame honoured her with induction in 1993. If you surf in Australia, then you should know something about Isabel Letham.

But who could have guessed what the immediate impact of catching those waves would be on Isabel's life? Isabel was already known locally as a sports mad tomboy and a bit of a dare devil, particularly in the water. She loved aquaplaning, body surfing, stunt swimming and diving, and, after the Duke's visit, Hawaiian surfing. She had a feisty, forthright personality that had been influenced by the feminist thinking of her mother and the various like-minded women who came regularly to meet at their house. And to top it all off, she was gorgeous.

So when someone suggested to Isabel that she might be able to make it in the movies, she decided to take the chance. After all, the afternoon surfing with the Duke had given her an international profile. The Los Angeles Record, for instance, described her as 'A Sydney Sea Gull' and 'Diana of the Waves'; she was the world's greatest stunt swimmer who 'became proficient at aqua-planing while dodging sharks in Sydney harbor'. The Hawaiian Star Bulletin claimed that 'As far as features go, Miss Lethem is the prettiest swimmer to come out of Australia. As for diving, she is another Annette Kellerman.' In a world where the popular press and movie houses were constantly on the look out for the next celebrity, Isabel had as much chance as the next lively young thing. The choice between taking on a year as a sport instructor in a Sydney girls' school or trying her luck in Hollywood, especially when her father was bankrolling the second option, was an easy one for Isabel to make. She left for the United States in 1918.

By all accounts, the journey across the Pacific and through the United States was marvelous fun. Isabel hobnobbed it with movie stars and directors and met members of the Russian aristocracy who were down to their last fur coat after fleeing the revolution. She traveled into Native American Territory and flirted with journalists and soldiers returning from the war in Europe. She didn't scimp on anything; she enjoyed being a young, modern woman, on her own, away from Australia. So certain was she that she would stay in America, she took our United States citizenship. She loved her life and loved where she was living.

Unfortunately, none of this 'networking' translated into serious work and her father, becoming impatient with her living it up without any return on his investment, decided he would no longer finance her trip. To make matters worse, she began to find life in Los Angeles less than perfect. As one report would have it, 'She found that distance had lent enchantment to many aspects of Hollywood.' So Isabel traveled north to San Francisco, which she liked better and where she had friends, and did what she had done as a young girl growing up in Sydney. She took to the water.

Reflecting on her life when she was in her eighties, Isabel observed that a key difference between the United States and Australia in the period between the wars was that 'the opportunities in the United States were high for women'. Given the way Letham's career developed in San Francisco during the 1920s, it is hardly surprising she came to that view. After first resorting to hairdressing to pay the rent, which she hated, she convinced the staff at the University of California at Berkeley to appoint her as an assistant teacher of swimming in 1923. She also taught swimming for the San Francisco playground commission during the summer of 1924. When the position of Director of Swimming for the City of San Francisco came up, she was immediately appointed to it. The results she was getting with her innovative, 'scientific' teaching methods had become common knowledge at Berkeley and amongst the parents of children who learned from her during the summer.

One of her first initiatives as director of swimming was to establish a club system like that which existed in Australia and a regular season of competition. Once this was up and running, she organized, in 1926, San Francisco's first women's competition; an invitational that involved local and national champions. The press were amazed by the speed with which she had improved the swimming of ordinary folk and elite sportspeople alike, certain that she had been 'instrumental in starting several of the present day champs on their careers'. Arguably, an Australian woman can claim some responsibility for the system that produces the champion swimmers of the United States today!

She tried to teach them a thing or two about surf life-saving as well but was stymied by, the rules of the Manly Surf Club, which reflected the prevailing views of women in the Australian Surf-Lifesaving movement that existed right up until the 1980s. In the 1920s, swimmers were so ill equipped to handle the California surf, and the surf life saving methods so inefficient, police actively discouraged people from swimming on the beaches because they could not guarantee their safety. Letham wanted to introduce Australian methods to the beaches of San Francisco and, in preparation for the task, applied for membership of her 'local' club, the Manly Surf Club, believing that she would carry more authority with the people of San Francisco, especially the police, if she could claim that qualification.

Her application was knocked back because she was a woman, which meant, according to the president of the club, she would not be able to handle the conditions in rough seas'. He argued this, despite the fact that Isabel had helped struggling swimmers in pools and in the surf for many years. Under the headline 'SEX BAN ON GIRL LIFE-SAVER, SO AUSTRALIA LOSES ADVERTISEMENT', the journalist for the San Francisco Daily News registered his disappointment. 'Although she has saved many lives she is not eligible for membership in a surf live-saving club on account of her sex,' he complained. 'In refusing Miss Letham the privileges of membership of the Manly Surf Club, the association, it is felt by beach-men generally, is losing an excellent opportunity of broadcasting Australian life-saving methods,' the report continued. No doubt this was one occasion where Isabel believed that relative to Australia, the United States was a land of opportunity for women!

Letham returned to Australia for a short visit in 1926 to a fair degree of press interest and a wealth of experience in sports administration she has gained whilst overseas. What she saw did not impress her much, and her public criticism may not have gone down particularly well with city developers here. She had a lot to say about the state of Melbourne's playgrounds and beaches, with which she was very disappointed. After swimming at St Kilda Beach she observed that 'There isn't a beach in California to equal those of Melbourne but civic enterprise has given California some of the finest bathing pools in the world.' Joking, she told observers that she would 'like to take St Kilda beach back to America with her when she returns. They would make SOME pool out of it,' she declared. She was similarly unimpressed by the lack of foreshore development around Brighton Beach.

In 1929, Isabel Letham returned to Sydney permanently. After hurting her back (she fell down an open manhole in the middle of a street), she was fearful of how an injured woman who relied on being physical for employment might survive without family, as the effects of the stock market crash began to be felt in the United States. She taught swimming at the Manly pool and wrote articles about swimming for the Manly Daily News. Years of getting into the pool with her students, rather than bellowing instructions from the edge, began to take their toll on her health. She suffered terrible rheumatoid arthritis and rheumatic fever. Between bouts of illness, however, she continued to teach. She was especially busy during World War 2, claiming that parents wanted their children to know how to swim 'in case the Japanese came'.

She also found a ready market for students to learn water ballet, which she had first seen performed the way she taught it in the United States. She opened the Freshwater Water Ballet school in the late 1940s. It could be said that Isabel Letham was responsible for bringing synchronized swimming to Australia. She is definitely responsible for safety and security of hundreds of people who grew up around Freshwater and the Manly and Curl Curl Swimming Pools. Throughout the 1930s, 40s and 50s, there would be few people learning to swim in those areas that didn't come in contact with her. As she herself said, 'Swimming instruction gave me the opportunity to meet all sorts of people in all sorts of places.'

She never had the opportunity to meet a husband, although, she hastened to add, that was not through want of suitors. The practicalities of wanting a career between the wars, and being an only child, intervened. She was too busy when she was young and then, when she was less busy her mother got ill and she needed to care for her. Before she knew it, 'The time just went by'. She added, however, that, it wasn't only practical considerations that kept her single. 'I was always looking for something I never found,' she said in her eighties, 'although I had some very interesting friendships'. Many of these friends remained close as she lived out her later years.

Surfing made Isabel Letham famous, and the ceremony she requested on the beach at Freshwater after she died in 1995 shows how important the surf was to her own sense of identity. Those 'interesting friends' who could, joined members of the local Freshwater community as they gathered for a ceremony at the beach, and her ashes were scattered in the midst of a circle of board-riders formed out the back of the surf-break. Those who attended claimed that at that time, the memories of the past and of the surfing history of Australia were rekindled.

But focusing on those four waves surfed with a man, even if it was someone as charming, skilled and intelligent as 'The Duke', has meant we have forgotten the extraordinary things that Isabel did as a single woman across two continents. Teaching the people of the city of San Francisco and the northern beaches of Sydney how to swim are no mean feats at all! Establishing a program to encourage the young women of California to swim competitively was a complex administrative task that continued to bear fruit well after she left the United States. It's sad to think, especially in the Year of the Surf Lifesaver, that the Manly Surf Club frustrated her efforts to make the beaches safe for the swimmers of San Francisco by not allowing her to officially import proven ideas and techniques from Australia. No doubt, were she alive today, Letham would be delighted with the international success of women like Carla Gilbert and Emma Snowsill, women for whom active and official participation in the surf lifesaving movement is central to the development of their sporting careers. Watching Snowsill's victory in the Commonwealth Games Triathlon in Melbourne last year; now that would have been something worth leaving the knitting for!

Images

Portrait of Isabel Letham; Isabel Letham and Pam Burridge, Freshwater Beach

Images Courtesy of Local Studies Collection, Warringah Library Service